(or: How I spent My WinterSpring SummerFall Vacation).

(This post is a revision of an earlier opus posted to coincide with the actual anniversary of the pandemic/quarantine. That version was more than 4,500 words. Shortly after I posted it I learned that the Nashville writers collective The Porch is compiling an anthology about the plague year, with a maximum word count for submissions of 3,000 words. So I cut and revised, submitted what follows on March 25, 2021, and still await a verdict re: acceptance or rejection. In the meantime, the guidelines say that posting to my own blog is ‘fair game.’)

*

1. Winter: #HomeAlone

March 13, 2021 marked a full year of the condition I’ve recorded in my journals and social media posts as “#HomeAlone.” I guess that was #HomeAlone Day 366 – since 2020 was a leap year.

Maybe it’s enough to say that a full year into the pandemic, I am still among the living. There are now more than two-and-a-half million Covid victims around the world who cannot say the same.

We have lived through a full cycle of seasons with Covid. It started in the winter of 2020, tore through the spring, the summer and the fall, and now here we are in the spring of 2021. Even with the vaccines, it could be a another full cycle before we can return to whatever passed for ‘normal’ before the virulent little bug first appeared.

Everybody on stage for the finale: Dave Olney tribute/memorial at the Belcourt – March 9, 2020

The last public event I attended was a tribute concert for the iconic singer/songwriter David Olney (Spotify link) – who died suddenly after collapsing on a stage in Florida in January, 2020. As friends and fans gathered the evening of Monday, March 9 at the Belcourt Theater in Nashville, there was casual recognition that something ominous was in the air, but it had yet to dawn on anyone that this might be the last concert we would attend for more than a year.

I worked my part-time job – peddling gizmos for a tech retailer – at the mall in Green Hills on Tuesday March 10 and Wednesday March 11 – which was the day the World Health Organization declared that the novel Corona virus had become a Global Pandemic. My customer interactions that day were normal, but I second-guessed myself after shaking hands a couple of times. By the end of the second day, co-workers and I had resorted to hand waves and fist bumps.

The next two days I was not scheduled to work. I watched too much TeeVee news, read too many online accounts, and tried to make sense of the invisible asteroid that was about to smash into the planet. I tried to separate useful information from the bubbling brew of hysteria. And I wondered how I was going to explain to my employer that because I was born while Harry S Truman was president, I am in the “high-risk-for-mortality” age bracket – and maybe I shouldn’t be coming into work for a while?

The day before my next scheduled shift, I called the store and said, “I’m a little concerned about coming to work today.” A few hours later the woman who runs the whole operation called back and said, “OK, we will take you off the schedule – and find someway to keep you on the payroll until you can come back.”

As I told my therapist at the time, that was such a moment of unexpected and unconditional support that it nearly brought me to tears. Actually, strike the “nearly.”

The next day my company closed all of its more than 300 stores in the U.S. and sent tens of thousands of employees home. The whole world went into panic mode and started running out of toilet paper.

And I started using the hashtag #HomeAlone. I’ll stop using it when I return to work in the store.

2. Spring: Expanding Waistline

I had started using a grocery delivery service a couple of months earlier; Once I entered the “I’m not leaving the house” zone, I came to rely even more heavily on such services.

Knowing the risks they were taking, I tipped the drivers generously. And I imagine I was quite the comic vision in bright yellow rubber gloves, washing and rinsing all the packages in the kitchen sink before putting them in the cupboards.

Thankfully, I already had more than enough toilet paper for the one person in the house who needs it once a day, but I might have started over-stocking on certain other staples. The freezer in my basement is still provisioned with a six-month supply of frozen proteins, and I still get weekly deliveries of fresh milk, orange juice, and eggs. And Oreos. Oreos have become my Quarantine Comfort food. I’m quite certain that I have single-handedly kept Nabisco in business for the past year.

It’s only a slight exaggeration to say that I really didn’t do much for the first few months besides eat. What I did do was get fat on Wheat Thins and cheese in the afternoons and a honkin’ bowl of Purity Cookies and Cream that I scarfed down with some late-night comedy around 10 o’clock every evening. From March to July I went from 173 pounds and jeans that were already a bit tight in the waist to 184 pounds – and the next size larger jeans.

Once it became apparent that nobody was going anywhere to do anything for months to come, the commentaries in my daily newsfeed ran the gamut from “don’t feel guilty about not doing anything during a pandemic!” to “use this time to do all the projects you’ve been putting off!” I did a bit of both.

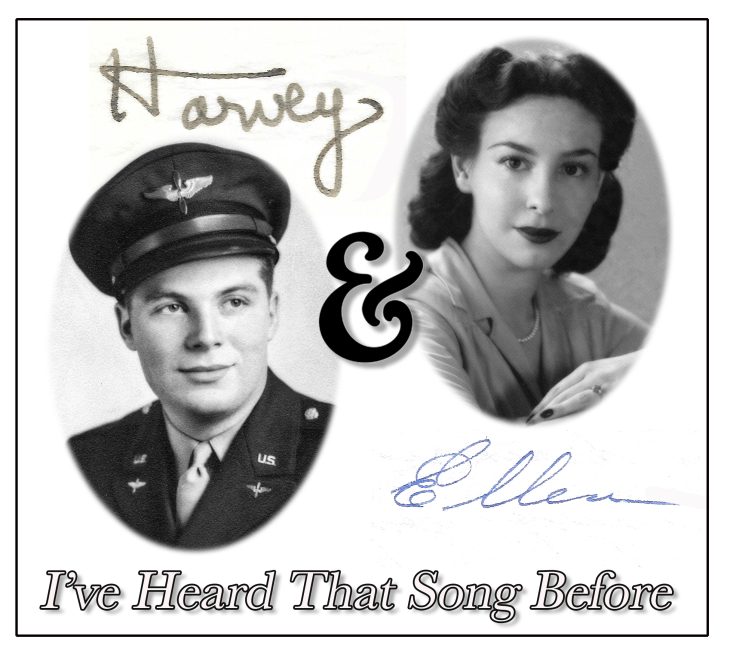

Harvey Schatzkin & Ellen Gould, ca. 1943

On the ‘get busy!’ front, I played my guitar some, and returned to a project that has been lurking on the back burner for a couple of years.

I have in my basement a scrapbook stuffed with all of the letters that my parents exchanged in 1943 – the year between when they met and when they were married in January of 1944.

Most of that time future-father Harvey was deployed to a weather station in Greenland (you’d be surprised how vital weather information from the arctic circle was to the aviation war effort in Europe); Future mother Ellen stayed home in St. Louis, and they exchanged the sort of letters that war-time love stories are made of.

A while back, I’d started reading those letters, using voice-recognition software to transcribe them into digital text. Now with nothing but time on my hands I returned to that undertaking, reading and dictating several of the letters every day.

Harvey and Ellen’s letters, aka “The Pile.”

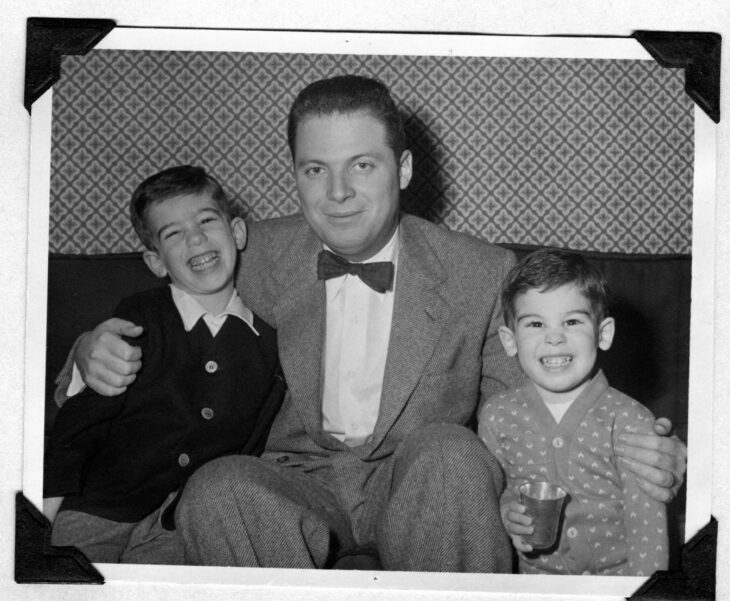

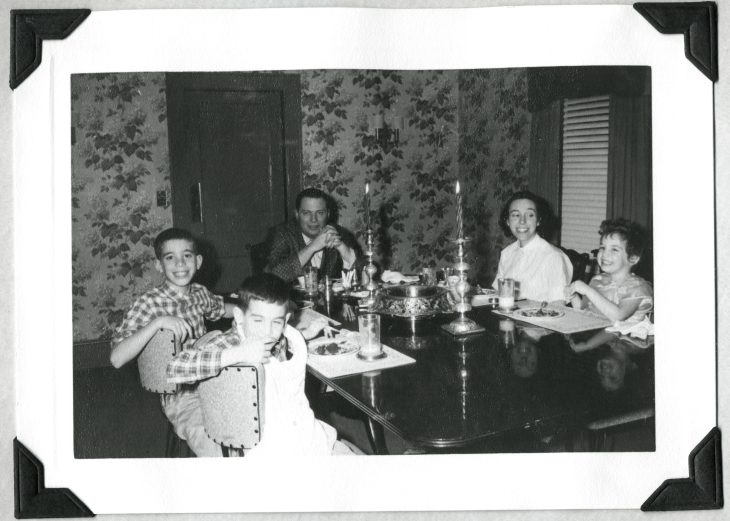

I am drawn to the letters in part because I never really knew my father. He died from cancer in 1958, at the age of 37; I was only 7 at the time – the age, my mother said later, when he was just starting to do things with me – like the night in October, 1957 when he took me out to see if we could find Sputnik wandering among the stars.

From his letters, I can tell that my father was a man of humor and depth – and was, uncommonly, passionately devoted to the woman he would marry and father three children with. Thanks to Covid and the afternoons spent combing through those letters, I have over the past year spent more time ‘in the presence of my father’ than I did in the few years when were both alive.

3. Summer: Life Is Better With The Top Down

As the months wore on, my part-time job went through numerous work-at-home iterations. To its credit, while millions were being fired or furloughed, my employer kept everybody on the payroll. But there really wasn’t a whole lot for us to do.

For the first few months, we did a lot of video conferencing, studying online manuals and guides to keep our knowledge and skills sharp in the event we returned to the store.

The store tried to reopen in the spring and called us all in for some “socially distanced” sales training.

It was weird driving into town for the first time in months, though it did occur to me that one upside of a global pandemic is the relative absence of traffic. It had been so long since I’d been to work, I had to consciously remind myself of the route that I take from my home in Pegram to the Mall in Green Hills: “Oh yeah, I get off the Interstate here… I turn here… wait, where the hell is everybody? Oh, look, plenty of places to park.”

Walking into the the Mall, I got my first taste of who was or was not wearing a mask – and I discovered how irritated I get whenever I see somebody with a mask that doesn’t cover their nose. I’m writing this nine months later and that still pisses me off – but I have learned to stifle my irritation – if barely.

With Covid case numbers still rising, the reopening date was postponed once… twice. When it was postponed the third time, they didn’t even bother to reschedule. The store stayed closed all summer and well into the fall.

In July, the company sent us specially configured computers so that we could join the online-and-telephone sales force. I am now a telemarketer.

I am genuinely grateful for the benefits my company has continued to provide – like health insurance (even though I am old enough to qualify for Medicare), weekly Covid tests and generous discounts on all the gizmos that I have come to rely on even more heavily in all these months of digitally-mediated isolation.

And I must admit that that those bi-weekly pay checks provide an essential buffer between daily deliveries from Amazon and having to compete with the cat for food.

When my shifts ended early enough – especially after Daylight Savings kicked in – I amused myself with almost daily drives in my Mustang convertible along the curvy backroads of this part of Tennessee on the outskirts of Nashville that I like to call “West Bumfuque.”

When there isn’t much else going on in your daily life, there is a lot to be said for putting on a cap and sunglasses, putting the top down – and downshifting and stepping on the gas coming out of the backcountry curves while a carefully curated playlist throbs from the stereo.

They said I’d never find what I was looking for: a Mustang Convertible with 6-speed manual transmission. But there it is, even in the color I wanted: Ruby-Fucking-Red.

Since there are no passing lanes along my routes, my idea of an “an achievement” in those days was going the whole 15 or 20 mile route without getting stuck behind a slower car in front of me. Suffice it to say my average speed was well above the posted limits.

Every such excursion reminded me how fortunate I am to live in the country, and offered a new appreciation for the fresh-cut fragrance of a farm no matter how fast I drove past it. But I did wonder if the people I zoomed past noticed, perhaps saying to one another “there goes that crazy guy in the red Mustang again!” – and again, and again.

I remember how anxious I was the first time I had to stop for gas. One of the info-nuggets that circulated during the early Days of Covid was that the virus could be transmitted through physical surfaces like a gas-pump handle. I adopted the practice of carrying my yellow rubber gloves with me when I went to the gas station. I panicked slightly one time when I left the store after paying and opened the door with my bare left hand instead of my gloved right.

Maybe it’s just fatigue after nearly a year, but I am less reluctant now to enter public spaces – though I still prefer curb-side delivery. Recently I ran to a restaurant in town to pick up a take-out order. While I was there I observed a surprising number of people seated at tables – and wondered if there was a revolver on each table with a single bullet in the chamber.

4. Fall: The Social Dilemma

Like everybody else in the world, I have defaulted to a virtual reality. Almost all of my social interaction is through screens of one kind or another. My laptop and tablet are always on, relentlessly tempting me into the bottomless abyss of doomscrolling.

Even more so than before the pandemic, Facebook has knotted itself into the daily fabric of my life. Here in the Covid Bunker, Facebook offers the persistent illusion of social contact and stimulation – in its compulsive, simulated way, filling the vacuum that forms in the absence of a real world.

It’s hard to separate the good that Facebook sometimes does from its insidious side-effects.

On the one hand, through Facebook I recently recently struck up a correspondence with a dear friend from junior high school I hadn’t spoken to for several years. When she wondered about my near daily #HomeAlone posts, I informed her of my divorce two years ago. We’re in the same boat, so to speak – only 2,000 miles apart.

There is also a group page keeps me connected with my neighborhood out here in West Bumfuque. Early in the lockdown, when the grocery stores ran out of staples, one of those neighbors supplied with me a huge bottle of ketchup.

On the other hand, Facebook is a relentless distraction, never more than a mouse-click away, and the cultural impact of its pernicious surveillance model has been widely documented.

I feel the same way about Facebook that I felt about Scotch and vodka before I quit drinking – but I’ve been saying that for years. For now, though, social media is the easiest place to go when I feel the need to unload some snark and irony – or if I just want people to see that I really – literally! – haven’t gone anywhere.

My “Work-At-Home” Station

My work has gone entirely online. Three-and-a-half days each week, I take calls from people all over the country, usually telling them why they are not going to get the gizmo they want when they want it – and asking sarcastic, rhetorical questions like “you do know we’re in the middle of a global pandemic, don’t you?”

Back in October, after one particularly arduous shift, a woman I’d ‘swiped right’ with started sending me text messages, and I just wasn’t in the mood.

That’s when I put a name on the condition that defines my year.

I have been living in an “Isolation Feedback Loop.”

I am alone, and, yes, it gets lonely. Now leave me alone.

5: Redux: Winter and Spring – Again

Given my age, the case numbers and the unfathomable death toll over the past year, I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that staying healthy has been no mean feat. As fellow Boomer Fran Lebowitz put it it in a recent NPR interview, “I think I’ve been excellent at not getting Covid – because I have not gotten it.”

Staying alive has mostly meant staying #HomeAlone. It’s just me and my screens and Buster the Demon Cat, who showed up over Memorial Day weekend thanks to a (mostly) Facebook friend. See? There’s that whole Facebook conundrum again.

Click the picture to see all the “Daily Buster”s

Buster is my constant companion, following me all over the house as I make my daily commutes from the bedroom to the kitchen to the office to the living room and back to the bedroom. Every morning begins with her nestled in my arms, nuzzling my chin and purring her little heart out while I type in my journal.

While friends and acquaintances have turned this year into a period of extraordinary output – writing books, writing and recording songs and posting an infinite stream of Facebook Lives and videos on YouTube – the only thing I have done with any consistency is make photos of Buster and put them on Instagram and Facebook. When my grandkids ask, “Grandpa, what did you do during the pandemic?” I’ll just say “I put cat pictures on the Internet.”

Oh, wait.. I don’t have any grandkids – even though I turned 70 back in November. I had a step-granddaughter for a while, but lost her in the divorce, too.

One upside of all this solitude was rediscovering extended, linear concentration in the form of an ancient information technology called “books” – which I read sitting on my deck, watching the sunset while hummingbirds hovered at the feeders overhead.

Honestly, it hasn’t been all solitude and screens. I’ve had a few lunches with friends – outside, on sunny autumn days. I’ve gone for hikes in the park. I have spoken with neighbors that I hadn’t spoken to since the divorce (“I got the house but she got the neighbors…”). And, speaking of my domicile, I see my housekeeper every other Tuesday. I can’t imagine the squalor I’d be living in were it not for her.

But I can count the total number of hugs I have had since March, 2020 on the fingers of one hand.

From peak-to-trough, minus 30+ lbs

At the end of July, my Wheat-Thins-and-Ice-Cream-Quarantine-Diet peaked the scale at almost 185 lbs, and even the expanded-waist jeans I was wearing were starting to bind. That’s when I decided to try a regimen “Interim Fasting” that I learned about – where else but? – on Facebook. In my case, “fasting” mostly means I stopped eating those honking bowls of ice-cream every night at 10:30.

I walk four to six miles around my neighborhood every day, repeating the route so often that I’m surprised there is no rut in the pavement. I use an app to count my calories, and on March 4 I hit my goal weight of 155 lbs – the first time my weight has had a “150-handle” since I was in my 20s.

As March, 2021 draws to a close, I am – thanks to my advanced age and, at last, a competent Federal government – fully vaccinated.

As the prospect of a return to some semblance of normalcy shines over the horizon, I am beginning to detect the visceral changes that this year has imposed. I seem to be going through the world very differently. Maybe spending an hour or two nearly every day just walking at three miles an hour has rewired my internal wheel-works. Maybe that explains why I have found new comfort in books and words on paper and less patience for words on screens.

A few weeks ago, some prophet scrawled on a New York subway wall that “after the plague came the Renaissance.” There is good reason now to shed the gloom of the past year and begin to imagine the world reborn – the bright light that will shine upon us as we emerge from this long, dark tunnel.

When the pandemic is over, I’ll be able to say that I survived. I hung out with my dead parents. I put cat pictures on the Internet. I kept my job and learned new skills. I lost 30 pounds. And I read more books in a year than I read in the five years prior.

I didn’t get sick, and I didn’t die.

Now, where are my shades?

The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls…