This is where the story begins, on a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean near Santa Cruz California, on a warm afternoon in the late summer of 1973.

I had graduated from a branch of Antioch College near Baltimore, Maryland, in the spring of 1973. In the course of what passed for my higher education – in between all the joints I rolled and smoked – I was one of an emerging global cadre of long-haired, hippie-radicale “video guerillas.” My classmates and I experimented with a new media paradigm, using the very first portable video recorders – the Sony Porta-Pak – to create programming for public access on cable TV.

Our text book through that era was periodical out of New York called “Radical Software.”

The 8th edition of Radical Software was published in the spring of 1973, just before I graduated from Antioch. That issue was dubbed the “VideoCity” edition” because – as I learned within its pages – electronic video was invented there in the 1920s.

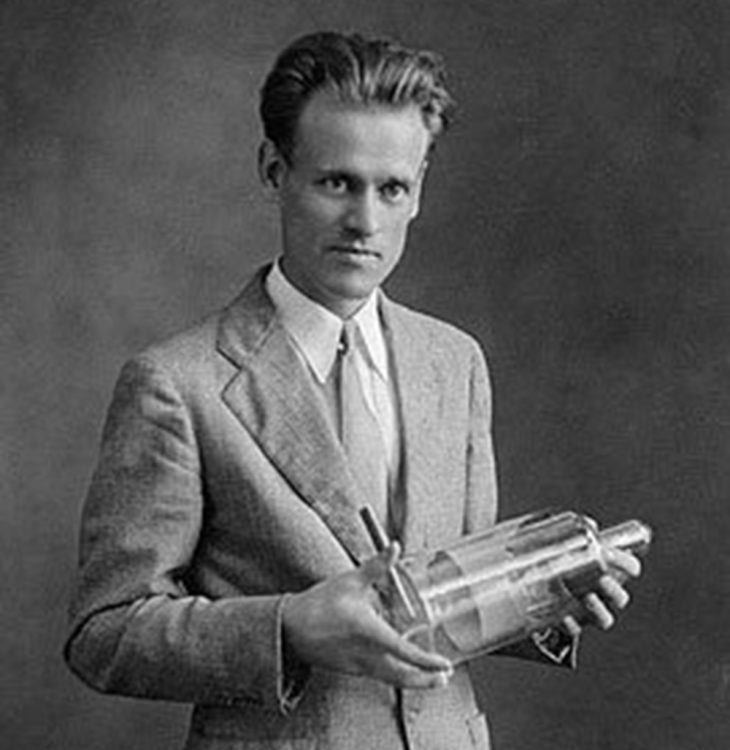

And that’s where first I encountered a name which would ultimately become a primary preoccupation of my adult life: Philo T. Farnsworth.

It was in these pages that I first learned of the 14 year old farm boy with the cartoon-character name who figured out in 1921 how to bounce electrons around in a vacuum tube in order to transmit moving pictures through the air. I learned about his struggles to perfect his invention and his fights with RCA over his patents. I saw images of a pre-history I had never seen before, and wondered then, as I still wonder now, why is his name not more familiar and why his story is not more frequently told.

After barely qualifying for a Bachelor’s degree (did I mention that I majored in joint-rolling?), I packed my guitar, a 35mm camera, a pair of hiking boots and a few changes of underwear into my Volkswagen Sqareback and spent the better part of the month of August driving across the country, intending to seek my fortune in the actual TeeVee industry in Hollywood.

When I arrived in Los Angeles at the end of August, I joined up with Tom Klein, my former college roommate, who was a native of LA, and we started working on some public access video projects out of Santa Monica.

Sometime in mid-September Tom and I took a little road trip up the California coast, to meet a fellow video guerilla who ran the public access cable channel in Santa Cruz and went by the assumed persona of “Johnny Videotape.” I have no recollection of this character’s actual name, so for the purposes of this story, we’ll just call him “Johnny.”

“Johnny” knew a fellow named Phil Geitzen, who had edited that “VideoCity” edition of Radical Software. And Geitzen was acquainted with Philo T. Farnsworth III – the oldest son of the Philo T. Farnsworth who had invented television, who had died in 1971, just a couple of years before all of this was happening.

Johnny and Tom and I went on a little hike through the Santa Cruz mountains, and stopped on a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

As the the three of us sat on a large rock amid the scuffy California brush, Johnny regaled us with stories that Phil Geitzen had heard from Philo T. Farnsworth (the third) about Philo T. Farnsworth (the second).

And it was there, on this hillside in Santa Cruz, looking out at the blue horizon in the late summer of 1973 that I first heard the expression “nuclear fusion.”

At a time when conventional nuclear power – what the Eisenhower era reverently extolled as “Atoms for Peace” – was just beginning to encounter cultural push back for its freshly perceived dangers – in other words, during the time when the expression “meltdown” was just beginning to enter the lexicon – I learned about the most fundamental force in the entire universe.

Johnny explained that “fusion” is the opposite of the more familiar “fission” that burns in the core of conventional nuclear power plants.

Fission splits heavy atoms like Uranium or Plutonium into lighter atoms; the combined mass of the split-off, lighter atoms is less than the mass of the original, heavier atoms, and that difference in mass is released as energy in accordance with Einstein’s famous formula, E=MC2.

For the record, fission does not exist anywhere in nature; its presence here on Earth is an entirely human fabrication.

Fusion, on the other hand, is the most natural and common phenomenon is the entire universe. Fusion is the process burning within our sun and every star in the heavens.

It seems as if God, when he got bored being God all by himself and set about to create a Universe that could provide some companionship, when he was sifting around for a way to “let there be light,” he actually started with the idea of fusion.

In The Beginning…

God must have said to himself, “First I’ll create hydrogen. Easy. One proton, one electron. Then I’ll add a neutron. Then I’ll take two of these hydrogen atoms and press them together into an entirely new element. The result will be all the heat and light I need to create an entire universe!

God clapped his big hands together, and the universe went “bang.”

That’s all God had to do. Create hydrogen atoms in infinite abundance and then hang gigantic balls of hydrogen thoughout his new Heavens, compressing those balls of gas with the gravity of their own mass until the atoms fused together into a second element and presto: there was light, and there was heat.

That’s all God had to do. Create hydrogen atoms in infinite abundance and then hang gigantic balls of hydrogen thoughout his new Heavens, compressing those balls of gas with the gravity of their own mass until the atoms fused together into a second element and presto: there was light, and there was heat.

And God saw that it was good.

Some 14 billion years later, human scientists would name that second element “helium” and a Jewish patent clerk in Germany would calculate the awesome amount of energy released in its forming in the most famous mathematical equation ever written.

Over eons the stars did the rest of the work: forging an entire atomic chart of other elements, and then condensing those elements into planets. Over the course of several billion years (which might seem a mere six or seven days to a cosmic diety…) that process would eventually, produce organic, carbon based “life” forms that could carry and transmit that same energy.

God finally had himself some company, and on the seventh day he threw a party.

Look out at the night sky, and all you see, as Carl Sagan might have put it, are billions and billions of deep space fusion reactors. Along with sex, fusion energy is the most natural creative force in the Universe.

*

OK, back to that bluff overlooking the Pacific in the late summer of 1973.

Fusion, as Johnny had learned from Phil Geitzen, as Geitzen had learned from Philo Farnsworth III, offers mankind the promise of a clean and (relatively?) safe source of industrial energy from a virtually infinite fuel source. The hydrogen isotopes in sea water – the most abundant resource on Earth – store enough fusion fuel to power advanced civilizations for millions of years. And even though fusion is an atomic reaction, it presents none of the hazards or toxic byproducts that fission plants produce.

Johnny Videotape explained to Tom Klein and I that modern science has been trying to harness this fusion energy for useful purposes here on Earth for several decades – the obvious assumption being that if we can harness fission to generate electricity, then surely we can harness fusion toward a similar end.

Or maybe not?

Science has figured out how to harness the very unnatural process of fission into both controlled and explosive devices. The controlled devices are all those nuclear power plants, all those Three Mile Islands, Chernobyls and Fukushimas – all those meltdowns waiting to happen, and all that radioactive garbage that nobody knows what to do with. The explosive devices, well, that’s Trinity and Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The only fusion devices mankind has managed to perfect are the explosive ones. The hydrogen bomb. The monster of incineration that its architect, Edward Teller, liked to call “The Super.” Great for wiping out entire cities; not so great for powering them.

A controlled fusion reaction, one that could produce the same megawatts of electricty that we can get out of a conventional nuclear power plant? That has proven much more difficult to deliver.

Because: As a heavenly star is a fusion reaction, so an earthbound fusion reaction is an artificial star – and thus presents a cosmic riddle:

How do you bottle a star?

What sort of vessel can you create that is capapble of containing a seething atomic inferno as hot as the sun? What sort of container could withstand such heat without disintegrating? Conversely, what sort of bottle could contain a star that would not ultimately extinguish the star simply by coming in contact with it?

That is the quandary that Johnny Videotape presented that warm afternoon on a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Santa Cruz, California in the summer of 1973.

And the reason Johnny was telling us all this was because he had learned from Phil Geitzen, who had learned from Philo T. Farnsworth III, that Philo T. Farnsworth II – the man who as a boy had invented television – had spent the final decades of his life solving the riddle!

Philo Farnsworth had figured out how to bottle a star.

Now the story becomes rather apocryphal. Here is the story Johnny told, as I recall it 46 years later:

Picture Philo T. Farnsworth working alone in a makeshift basement laboratory.

In the doorway, his young son reverently stands by and watches as his father fires up his fantastic ‘star-making machinery.’ Before their eyes, the unthinkable materializes: the artificial star.

Together they watch the vibrant, shimmering light, and a knowing gaze passes between father and son.

When he is satisfied that he has done all that he can do and seen all he needs to see, the father shuts off the machine – and begins to dismantle it.

He removes a critical piece from the machine, and places it on a high shelf somewhere in the lab where nobody will ever find it – so that the machine will never operate again.

And then he takes the secret to his grave.

That story landed like a harpoon in my heart.

I am hooked on it still.

And that is why the website fusor.net has been around for more than 20 years.

And why I have been telling this story to anybody who’ll listen for nearly 50 years.

It’s an odd obsession, to put it mildly.

*

Two years after that afternoon in Santa Cruz, I tracked down the family of Philo T. Farnsworth.

In the pursuit of the fortune that had lured me to Hollywood, I had landed on the idea of making “a movie for television about the boy who invented it.”

That project has its own curious origin-and-dead-end story; That the most effective story-telling medium ever devised has yet to tell the story of its own fascinating origins remains its own bizarre mystery.

Pem Farnsworth, ca. 1977, at the dedication of the historic monument at 202 Green Street, where electronic video made its first appearance on Earth on Sept 7, 1927.

For now, suffice it to say that in July of 1975 I flew to Salt Lake City, where I was greeted in a modest-but-cluttered home by Philo Farnsworth’s widow Pem and two of her skeptical sons – the oldest, the aforememtiomed Philo T. Farnsworth III, born in 1929, and Kent, the youngest who was roughly my age. That trio of Farmsworths were the primary keepers of the family treasures (they are all deceased now).

Over the course of the next two days – and the next several years – I began to learn the untold story of the true origins of electronic video, and of the titanic struggles that accompanied its arrival in the world during the 1930s.

And over the course of those years Philo T. Farnsworth III became one of my best friends.

There are so. many. stories. I wish I had time to tell you the story of “The Prince, The Inventor, and The Egg.” I can only say now that Philo was one of the most unique individuals I have ever had the privilege of knowing until his untimely death in 1987.

Philo possessed unique insights into his father’s legacy. Though P3 (as he was often called) lacked his father’s mathematical prowess, he was an inventor in his own right and offered me keen insights into the inventive process that inform my own work to this day.

But in those first encounters, it became readily apparent that the entire family, and Philo III in particular, were fervently protective of their father’s legacy, and from the outset quite reluctant to discuss the fusion research – the star in a jar – that consumed the final decades of his father’s life.

But over time, time I would earn the family’s trust and learn the truth underlying that apocryphal story.

As we got to know and become comfortable with each other, I finally got around to telling Philo the story that Johnny Videotape had told me, the story that he had heard from Phil Geitzen that Phil Geitzen had supposedly heard from the lips of this very same Philo Farnsworth III.

Philo chuckled.

The story, he said, was indeed apocryphal, and perhaps a bit broadly drawn. The details were well off – Philo III was hardly a child, he was in his mid 30s during the years when his father was experimenting with fusion. But he also confirmed its essence when he said, simply, that “the patents are incomplete.”

Think of a patent as a text book. A well written patent should instruct somebody skilled in the underlying arts how to build the novel device disclosed therein. But if critical details are left out of the patent, even the most skilled practitioner will be building a device that falls short of its intended purpose.

In other words, filing an incomplete patent is much like taking a critical piece out of the machine and placing on a high shelf where nobody will ever find it.

Philo first told me about those incomplete patents sometime in the mid 1970s. But it was another 15 years before Pem Farnsworth, who had been at her husbands’s side during all the important moments in his career, would confide in me the story that is the climax of his biography.

In the summer of 1989, I returned to Salt Lake to help Pem and youngest son Kent put the finishing touches on “Distant Vision” – the memoir that Pem had begun writing when I first met her in 1975.

And when we got to the “second chapter” – the decade devoted to fusion energy research – Kent and I could both tell that Pem was withholding something, a critical detail she was reluctant to divulge.

Finally, we sat Pem down with a cassette recorder and coaxed from her the story of a night in 1965, when Philo brought her back to his laboratory that was, in fact, in a basement in Fort Wayne Indiana. Once past the night watchman and settled in behind the controls, Farnsworth opened the electrical ciruits feeding the reactor and adjusted the controls. And then the strangest thing happened: he withdrew the electrical current, and the reaction just kept on going.

Pem and Philo watched as the needles in various gauges pinned at the limits. And when the needles finally settled down, Pem told us that her husband turned to her and said, “I have seen all I need to see…”

Weeks later, he filed the patents that his son descibed to me as “incomplete.”

It is quite common when reading of contemporary fusion research to encounter the skeptical caveat that “fusion energy is 20 years in the future and always will be…”

But I have met the family of Philo T. Farnsworth – the man who, as a boy, arrived on this planet with the unique insights that delivered electronic video to the world. I have looked them all in the eye and I have seen and felt the abiding reverence they hold for the legacy they are protecting and the secrets that Philo T. Farnsworth took to his grave.

And I share their conviction: fusion energy is not 20 years in the future.

The path to fusion energy was found 50 years ago and we missed it.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Above, “Star Mode” in one of the many amateur and student science projects

that have kept Farnsworth’s approach to fusion alive for the past 20 years.

This work has been fostered by a website I created in 1998: Fusor.net