I think I’m goin’ back

To the things I learned so well in my youth

I think I’m returning to those days

When I was young enough to know the truth

Now there are no games to only pass the time

No more electric trains, no more trees to climb

Thinking young and growing older is no sin

And I can play the game of life to win

–– Carol King

For Christmas in 1954, my father bought, set up and gave to my older brother an elaborate set of Lionel trains, tracks, and accessories.

In our family photo albums, there is just one photo of Harvey operating the trains, my brother Arthur looking on in gleeful fascination as the cast iron 736 Berkshire electric locomotive “steams” by; Just out of the frame, circles of chemical-pellet induced smoke are puffing out of its little smokestack.

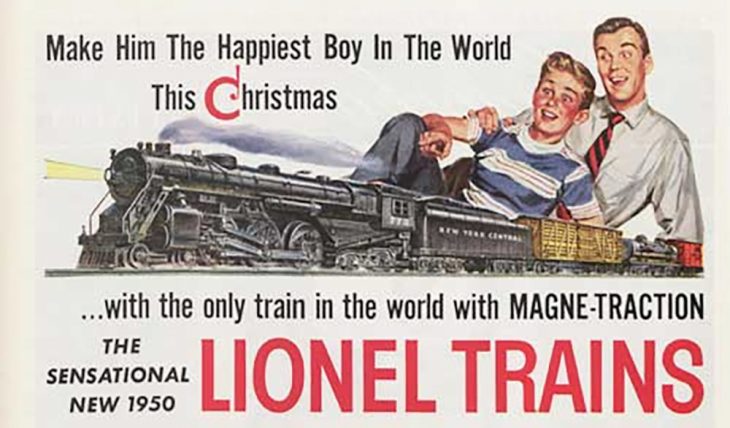

In the 1950s, Lionel trains were the quintessential under-the-tree expression of America’s post-war prosperity. The Lionel Corporation had found a way to flourish during the war, by retooling their assembly lines to manufacture servo motors for military equipment instead of electric motors for toy trains. Once the war ended, the company repurposed those servo motors in the first post-war generation of its marquee product.

Our family was sufficiently prosperous (the family business produced ceramic household tile at a plant in Keyport, New Jersey) that our parents could afford to give their kids the very best: that Berkshire locomotive with its smoke puffing stack and whistling coal car was top-of-the-line, but that was just the start of the layout. Arrayed within the circle of tracks were equally high-end accessories:

– A cattle loader with a vibrating surface that propelled little rubber “cattle” into a plastic cattle car;

– A milk car with a solenoid-powered mechanism that ejected little metal milk cans onto a little metal platform. The milk cans were cleverly made with a tiny magnet underneath so that they would stick to the metal platform when they came flying out of the milk car and not fall over;

– The log loader that carried wooden dowels up a conveyor belt and dumped them on to the waiting “log car” below;

– A light tower with a red-and-blue beacon that rotated just from the heat rising from the little lightbulb within;

There were several crossing gates and switch tracks to reroute the train from one circuit to another. It was all very elegant – lavish, even – and no doubt very costly, but the Schatzkin family could easily afford it.

All of this mid-century amusement was mounted atop an 8×8 foot table that was actually two standard 4×8 plywood sheets to which my father – an amateur carpenter of sorts who kept an extensive wood shop in our basement – had added a strip of smooth molding around the edges and then clipped the two sheets together with brass hooks. The whole assembly lay atop two folding aluminum tables which were also de-riguer household items in the 50s.

For that Christmas, the trains were set up in a (more typical 50s) wood-paneled room behind the living room that was called “the playroom.” There is only one other photo of the trains in our family albums; In it you can see 6-year-old Arthur gingerly pushing the throttle forward on the state-of-the-art transformer. You can also see some of the accessories that came with the trains.

After Christmas, the trains were taken down and reassembled in the basement. I honestly don’t remember a whole lot about them after that. What do you want from me, I was only four years old and this was all more than 60 years ago…

But I do remember that one morning in 1956 or ’57, the whole set up just disappeared.

*

In later years, our mother would occasionally tell the story of what happened to the electric trains.

One night, the story goes, my parents went to a dinner party at the home of Connie and George Selby (their their actual name was Seligman but at some point in the 50s they Anglicized it to “Selby” – my parents suspected they wanted a name that didn’t sound so… well… Jewish).

George Sr. went by the nickname of “Dink,” so – dumb as it sounds – we’ll just call him that. Dink and Connie had a son, George Jr., who was Arthur’s age. They also had an elaborate Lionel train set in their basement. I have some vague memories of seeing the Seligman/Selby’s trains, and of being envious of how much more intricate their layout was compared to ours. There were multiple trains navigating through realistic scenery, the tracks rising and falling through multiple levels on plastic trestles. Maybe this is how the Jews kept up with the Joneses in mid-50s surbubia – with dueling Lionel train sets; the gentile neighbors who lived on either side of our house all had Lionel trains, too.

The way my mother told the story, they were George Jr.’s trains but… Dink didn’t really let his son play with them. Dink ran the show and George Jr. was pretty much relegated to watching the trains go by.

The spectacle of a 30-something-year-old man commandeering his nine year old son’s electric trains was enough to send my father into a fit of pique.

And so, the story goes, my father came home that night so incensed that he went straight into the basement and dismantled the entire Lionel layout that he had set up for Arthur, and stuffed everything – the locomotive, the coal car, the milk car, the cattle car, the transformer and all the accessories – into a cabinet. The next morning he announced that “if you want to play with the trains, you’ll have to put them back together yourself…”

Which my brother never did.

The Lionels stayed dismantled and stashed in the cabinet in the basement where my father put them for several years.

They still hadn’t come out of those cabinets when Harvey died in the fall of 1958. He was 37. Arthur was 10. I was 7. Our little sister Dorothy – aka “Itsy Bitsy Dotsie (and there’s a story there, too) – was 4-1/2.

Fast forward with me now, all the way to 1959:

I’m in the third grade and for some reason that I will never recall I went down to the basement and got my father’s Lionel trains out of the cabinet where he had left them. Without any instruction or coaching I put the tracks together and connected all the wires and for the first time in years the Monmouth Avenue Railroad was running again. Hey, look, there’ the old 736 Berkshire, and the milk car and the cattle car and the log loader, and the crossing gates, and the little blue plastic man popping out of his miniature green-and-red gate house, swinging his little plastic lantern…

After that, the trains became “my thing” until we moved from Rumson to Maplewood in the spring of 1962. Before that move, my mother hired a noted photographer to come to our house to make portraits of the family. The photographer asked what I was interested in and I showed him the trains in the basement. He posed me with that cast iron locomotive.

*

I told my therapist parts of this story last week.

We talk a lot about my father.

More than anything my father longed for a creative life. Like me, he was a writer and a photographer, but he spent his (short) career making tile for kitchens and bathrooms. He was never published – unless you count the time that a letter he wrote to Macy’s was used for an ad in the New York Herald Tribune – but I’ve got a trove of his comic short stories in my basement that are still funny.

Almost 60 years after he departed from this planet, I still wonder how my life might have been different if he’d stuck around – at least long enough to see that <I> was the one who was destined to play with his electric trains.

I think he would have approved. And we would have had something to bond over, at least for a few years.

My mother often said of my father that “you were just getting to an age where he could do things with you…” when cancer dispatched his 37-year-old soul. I have only a handful of actual memories of him. One, in particular:

It’s October, 1955. I’m four, not quite five years old. The Russians have just beaten the US into space with the launch of Sputnik, Earth’s first man-made moon. One cold autumn night, my father took me – just me – out to the nearby high school football field to see if we could spot Sputnik wandering among the stars. We never did see the satellite, but the moment left an impression that remains vivid to this day. Now every time I look up at the stars… I’m back on that football field with my father.

I wish he could have been around for the moon landing in 1969. I think we might have watched it together. Oh, sure, there was a lot of other stuff going on at the time; I shudder to think what he, a World War II veteran, would have thought of his sons’ resistance to the draft and the war in Vietnam. And then I think: Maybe it is fitting that only the good die young. That way we never have pictures of them as angry, bitter old men yelling at us from the other side of the “generation gap.”

And I remember when I showed my mother my first personal computer in 1979. As I showed her how I could enter text and then wipe it off the screen with a single press of the “delete” key, she said, “your father would have loved this…” Really. He was what we now call a gadget freak. From Lionel trains to computers… we would have had that much in common.

*

I have been struggling of late with the whole idea of… approval. Of claiming and manifesting my creative instincts. And trying to not feel undeservedly pretentious about saying even that.

Creative types. We’re wired differently. And we go through life seeking validation and approval from – ironically – the more conventionally wired. I have spent my entire life doubting my creative instincts, even when they are clearly manifest. Like every writer (?) I finish one thing and wonder if there’s anything left. It hasn’t helped that my greatest success as a writer was followed by my most disappointing failure. Is it any wonder that infinite doubt ensues?

There was an odd little series on Netflix this year called “The OA” that, among other things, addressed the theme of the “invisible self.” In an early episode, the principle character, a young woman named Prairie, cautions a companion to be gentle with his own inner forces:

“You don’t want to go there,” Prairie cautions, “until your invisible self is more developed anyway. You know, your longing, things you tell no one else about?”

All this business about my father and his electric trains came up when I was telling my therapist that lately I, too have been feeling… invisible. It seems at times that I am just unwilling or unable to inhabit my own soul. Like there is some creature inside me that I am the only one who can see – and not altogether clearly at that. And that the people around me – even the people closest to me – want to reflect back on me… not my invisible self, but theirs.

I realize it’s mostly pointless at this point in my life, but still I can’t help but wonder: If my father had been around to see me set up and run those electric trains…. would he have approved? Would he have seen a reflection of himself, and in that reflection beamed back a glimpse of the invisible me? Maybe that glimpse, however brief and fleeting, might have provided enough recognition and approval that I wouldn’t still be longing for it 60 years later. His validation in that moment could have left a lasting impression, much like that cold night when a young father and his little boy scanned the heavens for a dot of light drifting among the stars.

*

When my family moved in the spring of 1962, the trains were dismantled again and packed into a box. Never mind that I didn’t get to pack the box; I was at summer camp when the family moved – but that’s whole other story.

Once I arrived at the new house, I don’t think I ever took the trains out of the box. By then my interests had shifted: I wanted slot cars, and my parents – that would be my mother and her new husband, aka my stepfather – told me I couldn’t have both. We sold the Lionels to a family from Newark for all of $75.

I’m sorry, Daddy. I don’t have your Lionels any more. But I still wish you had been around when I started playing with them.

*